I’ve returned from my first Mardi Gras. In the American imagination, “New Orleans” is an infinitely complicated amalgam of the actual place, its people, its terribly violent history – and the projections laid upon it by the rest of the country. Puritan America needed a place where its unacknowledged ecstatic (both sexual and spiritual) drives could be both loved and demonized. And for two hundred years, at least until the advent of Las Vegas, New Orleans was that place, the place where good, hard-working people went for a temporary, fairly safe vacation in chaos.

As such, it was and remains white America’s primary destination of pilgrimage. It was no accident that our language uses the word “spirits” for alcohol. And New Orleans is certainly full of spirits, in each sense of the word.

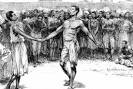

Escaping the madness (again: in each sense of the word) of the French Quarter, I crossed Rampart Street, where the actual city walls once were, to the quiet of Louis Armstrong Park. There, I came to Congo Square, where, on Sundays throughout the nineteenth century, slaves were allowed to congregate by the hundreds to drum and dance, watched over by white police and an encircling throng of white spectators. (Prior to those times, the Oumas Indians had used the field for their sacred corn feasts).

In 1853, an observer described the scene:

Let a stranger to New Orleans visit of an afternoon of one of its holy days, the public squares in the lower portion of the city, and he will find them filled with its African population, tricked out with every variety of show costume, joyous, wild, and in the full exercise of real saturnalia…Upon entering the square, the visitor finds the multitude packed in groups of close, narrow circles, of a central area of only a few feet; and there in the center of each circle sits the musician, astride a barrel, strong-headed, which he beats with two sticks, to a strange measure incessantly, like mad, for hours together, while the perspiration literally rolls in streams and wets the ground; and there, labor the dancers male and female, under an inspiration of possession, which takes from their limbs all sense of weariness, and gives to them a rapidity and a duration of motion that will hardly be found elsewhere outside of mere machinery.

The best piece of writing on the significance of Congo Square, indeed the very best essay I have ever read is Michael Ventura’s Hear That Long Snake Moan, which deeply influenced the writing of my book. Ventura writes:

The dances were an attempt by the city government to deal with the increase in Voodoo that had resulted from the recent Haitian immigration. It was feared that Voodoo meetings were being held to work sorcery against whites, and perhaps to plot revolution, so in 1817 the Municipal Council forbade slaves to congregate for any reason, including dancing, except in designated places on Sundays. Congo Square was the major place…

This is the way of things. It was precisely by trying to stop Voodoo that, for the first time in the New World, African music and dancing was presented both for Africans and whites as an end in itself, a form of its own. Here was the metaphysics of Africa set loose from the forms of Africa. For this form of performance wasn’t African. In the ceremonies of Voodoo there is no audience. Some may dance and some may watch, but those roles may change several times in a ceremony, and all are participants. In Congo Square, African music was put into a Western form of presentation. From 1817 until the early 1870s, these dances went on with few interruptions, the dance and music focused upon for their own sake by both participants and spectators. It is likely that this was the first time blacks became aware of the music as music instead of strictly as a part of ceremony. Which means that in Congo Square, African metaphysics first became subsumed in the music. A secret within the music instead of the object of the music. A possibility embodied by the music, instead of the music existing strictly as this metaphysics’ technique. On the one hand, something marvelous was lost. On the other, only by separating the music from the religion could either the music or metaphysics within it leave their origins and deeply influence a wider sphere.

And what was that wider sphere? America, and by extension (through music and film), the entire world. For Congo Square was the place where Jazz and Blues were born, out of that music the slaves made, and eventually Rock n’ Roll. As Ventura and I (in my book, especially Chapter Eleven) argue, it has been and will continue to be this influence of the African metaphysics upon an America defined by a separation of body and mind that will be the source of healing for us all.

I thought of all this as I sat quietly on a bench. But more importantly, I could feel the extraordinary energy of the place. Because this is where the spirits of those thousands of African-Americans who danced all those years – to forget their troubles, to contact their ancestors, to attempt to find some peace within the horrors of slavery – reside. The grief is palpable. I wept for them, for the victims of Hurricane Katrina and gang violence, and for all of us who have been willing to settle for the deeply diminished life of white privilege. Along with the tears, the phrase came to me: This is the dancing ground at the end of the world.

But when (as Africa has always tried to teach us) we allow ourselves to grieve fully, we may be blessed by an experience of joy and ecstasy equal in intensity to our sadness. Congo Square is still a place of pilgrimage.

In its center is a fountain (where one can easily imagine the great Voodoo queen Marie Laveau presiding over the ritual), surrounded by a couple of dozen manholes (can you see the drummers around her?). The surface of the square is covered with hundreds of six-inch rectangular paving stones. And the stones are arranged into a series of scallop-shell shapes that radiate out and down from the center in all directions. They flow like water, like tears, and seem to carry both the grief and the blessings (the latter impossible without the former) out into the city and the world.

Perhaps one day all those drunken revelers on Bourbon Street will realize that the “spirits” they seek are actually in this park only three blocks away. This is the dancing ground at the end of the world, where our world of racism, violence, consumerism, addiction and fundamentalism will end, dissolving into the source of the dance.

Pingback: Barry’s Blog # 258: A Vacation in Chaos, Part One of Four – Barry Spector’s Blog